The Role of Personality, Authoritarianism and Cognition in the United Kingdom’s 2016 Referendum on European Union Membership

Chris Sumner, John E. Scofield, Erin M. Buchanan, Mimi-Rose Evans, Matthew Shearing

Published 3rd July 2018 | Last updated 19th August 2023

Between April 9th 2016 and June 23rd 2016, we conducted six studies in relation to the UK’s referendum on EU Membership and previously shared preliminary results here (16th June 2016) and here (26th April 2017). In this article, we provide a technical summary of the results. Detailed results are available in our working paper (5th July 2018) and our peer reviewed paper published by Frontiers in Psychology (22nd March 2023).

Research Summary

In six separate studies, with a total of 11,225 participants, the Online Privacy Foundation (OPF) examined the differences in personality, authoritarianism, numeracy, thinking styles and biases between voters intending to vote ‘Remain’ versus voters intending to vote ‘Leave’ in the UK’s 2016 referendum on its EU membership. The studies form part of a larger OPF research project which seeks to understand the extent to which these biases and traits could be targeted and manipulated online.

The UK electorate’s views of EU membership appear to be strongly influenced according to people’s personality traits, dispositions and thinking styles. Participants expressing an intent to vote to leave the EU reported significantly higher levels of authoritarianism and conscientiousness, and lower levels of openness and neuroticism than voters expressing an intent to vote to remain in the EU. When compared with Remain voters, Leave voters displayed significantly lower levels of numeracy and appeared more reliant on impulsive System 1 thinking. In the experimental studies, voters on both sides were found to be susceptible to the cognitive biases tested, but often, unexpectedly, to different degrees.

Gaining a deeper understanding of the differences and similarities between Leave and Remain voters is an important area of study, not only to better understand UK society, but also to contribute to research exploring the effectiveness of psychographic targeting. In light of allegations of psychographic targeting during the referendum, it is important to understand whether, and to what extent, knowledge of voters’ core psychological characteristics and biases could be exploited, particularly through social media, to influence the way they form early opinions and subsequently process information.

The findings from this research raise important questions regarding the use and framing of numerical and non-numerical data during UK political campaigns. In a situation where “In general, political campaign material in the UK is not regulated, and it is a matter for voters to decide on the basis of such material whether they consider it accurate or not” (The Electoral Commission, 2018) the research also raises the question of whether existing regulatory controls need to be amended. Not only do many voters lack the skills to critically evaluate the information which is being presented, their inherent beliefs and biases clearly influence the way in which they process this information. Considering these factors, a fundamental question is raised as to whether direct democracy in the form of binary, winner-takes-all, referendums is an appropriate mechanism for deciding major and complicated political issues, such as constitutional changes. More broadly, constitutions may need to be adapted to take into account fundamental shifts in societies’ use of technology and consumption of information.

Results (Click images to enlarge)

Summary

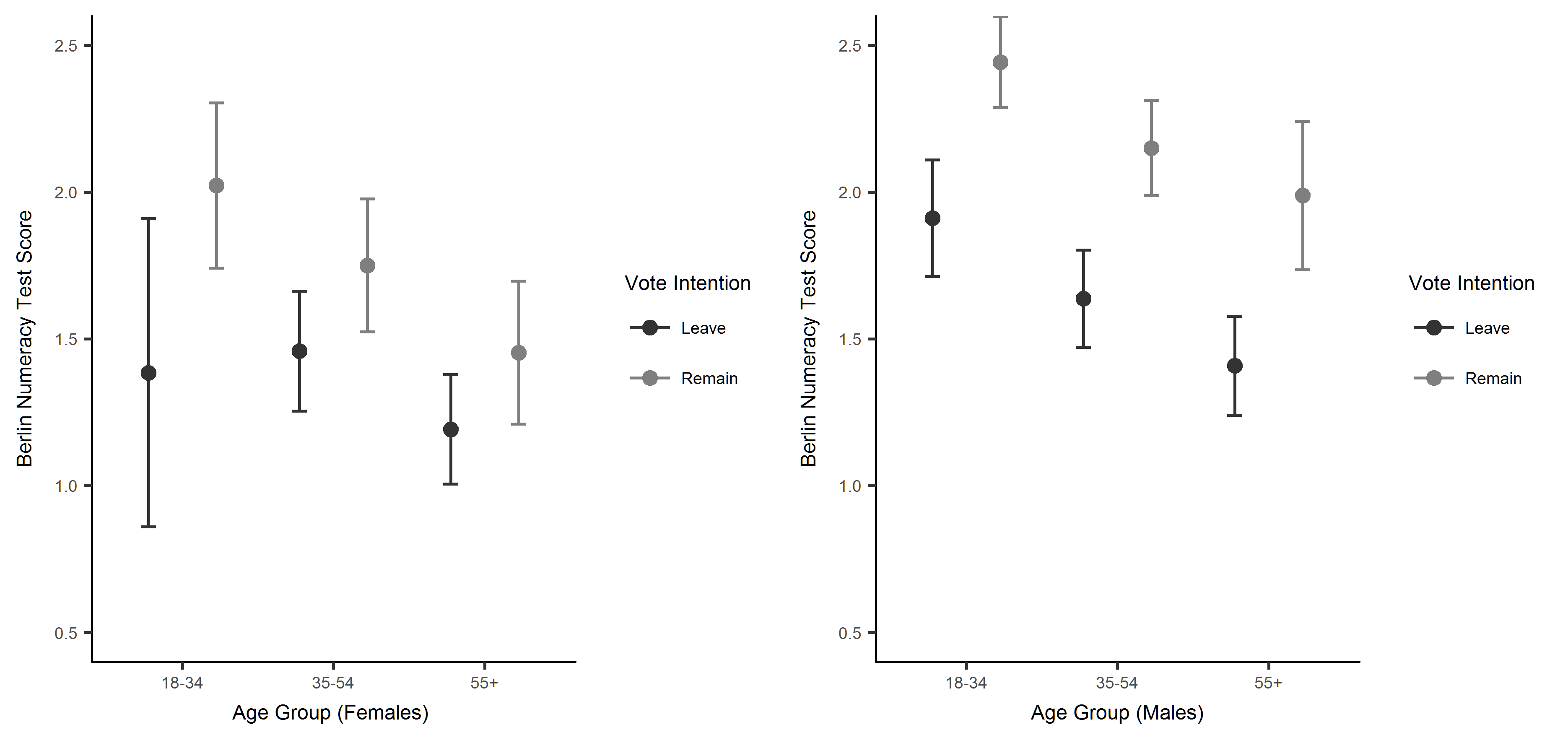

Figure 1. Summary of effect sizes illustrating the degree to which personality traits, authoritarianism and cognition differ between Leave and Remain voters. Effect sizes are normalized to Cohen’s d for illustrative purposes. See the notes section towards the bottom of this page for more information on effect sizes and a note on the large effect size observed with authoritarianism using the RWA scale.

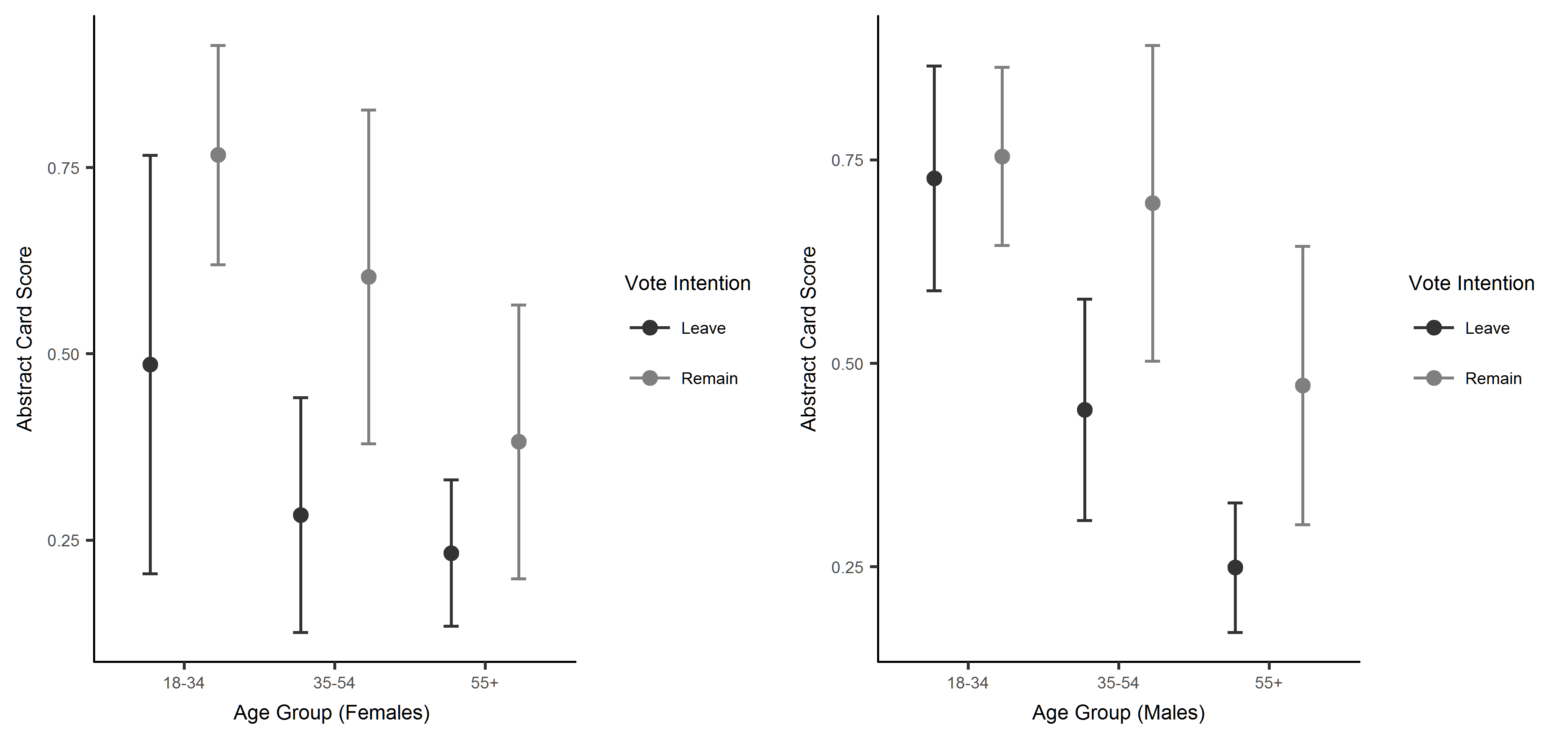

Figure 2. Summary of effect sizes illustrating the degree to which Leave and Remain voters were influenced by cognitive biases. Effect sizes are normalized to Cohen’s d for illustrative purposes.

Personality (Click images to enlarge)

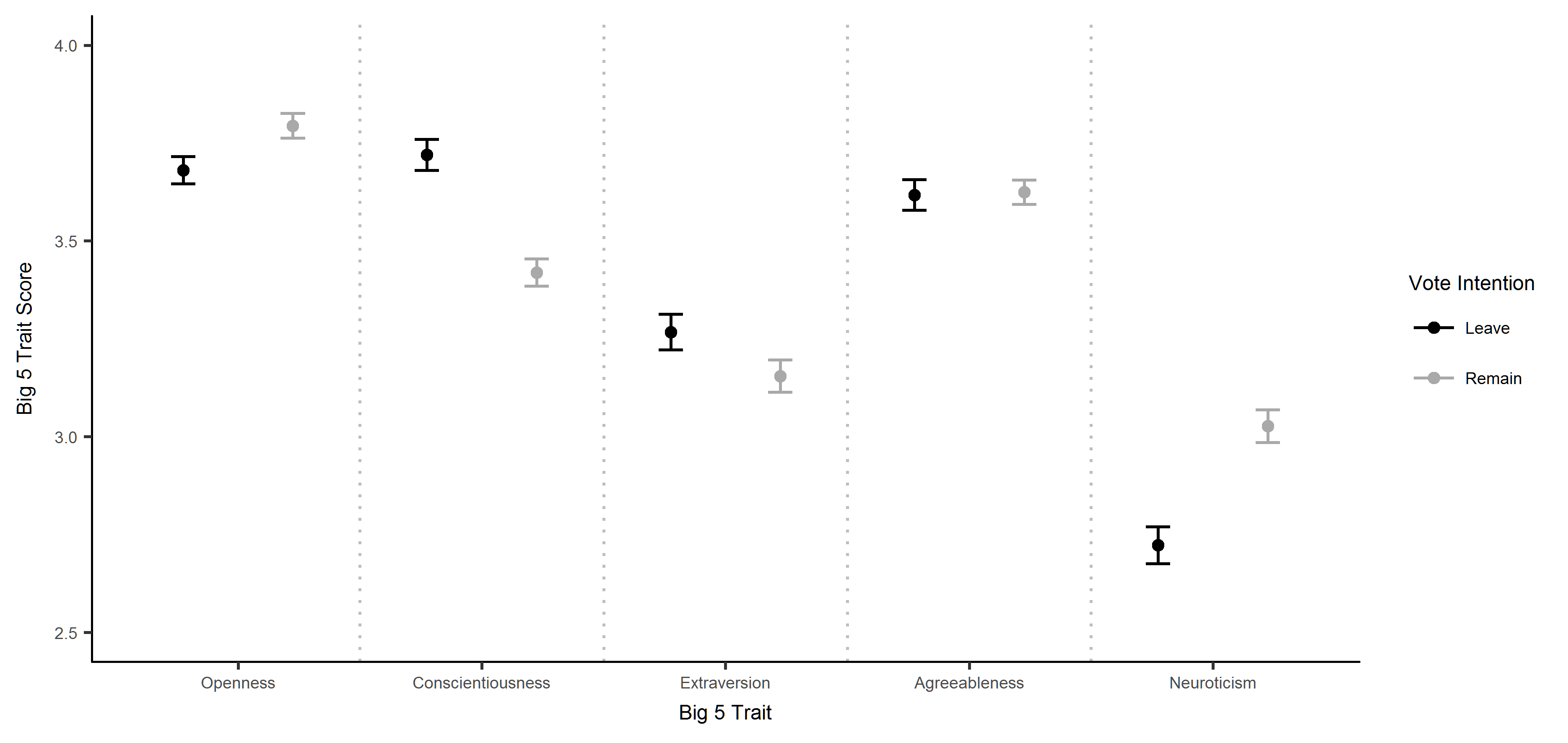

Participants expressing an intent to vote to leave the EU reported significantly higher levels of conscientiousness, and lower levels of neuroticism and openness than voters expressing an intent to vote to remain.

Figure 3. Vote intention by Big Five personality scores. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval of the mean.

Authoritarianism (Click images to enlarge)

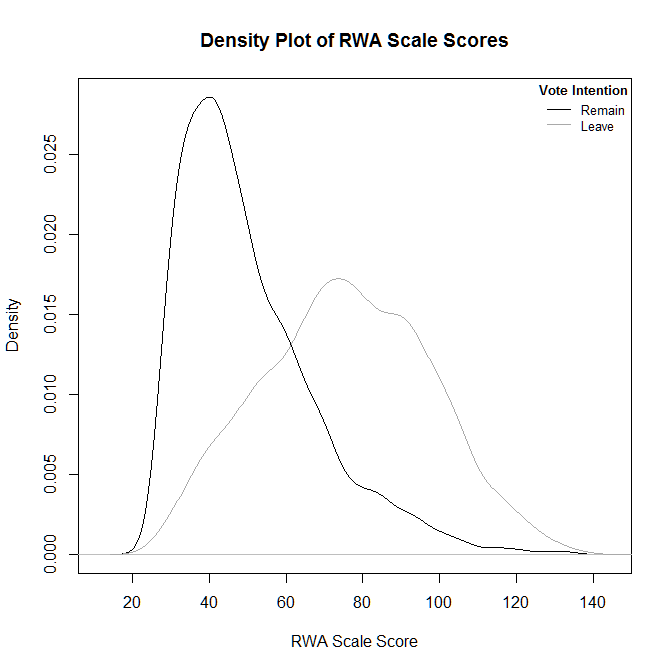

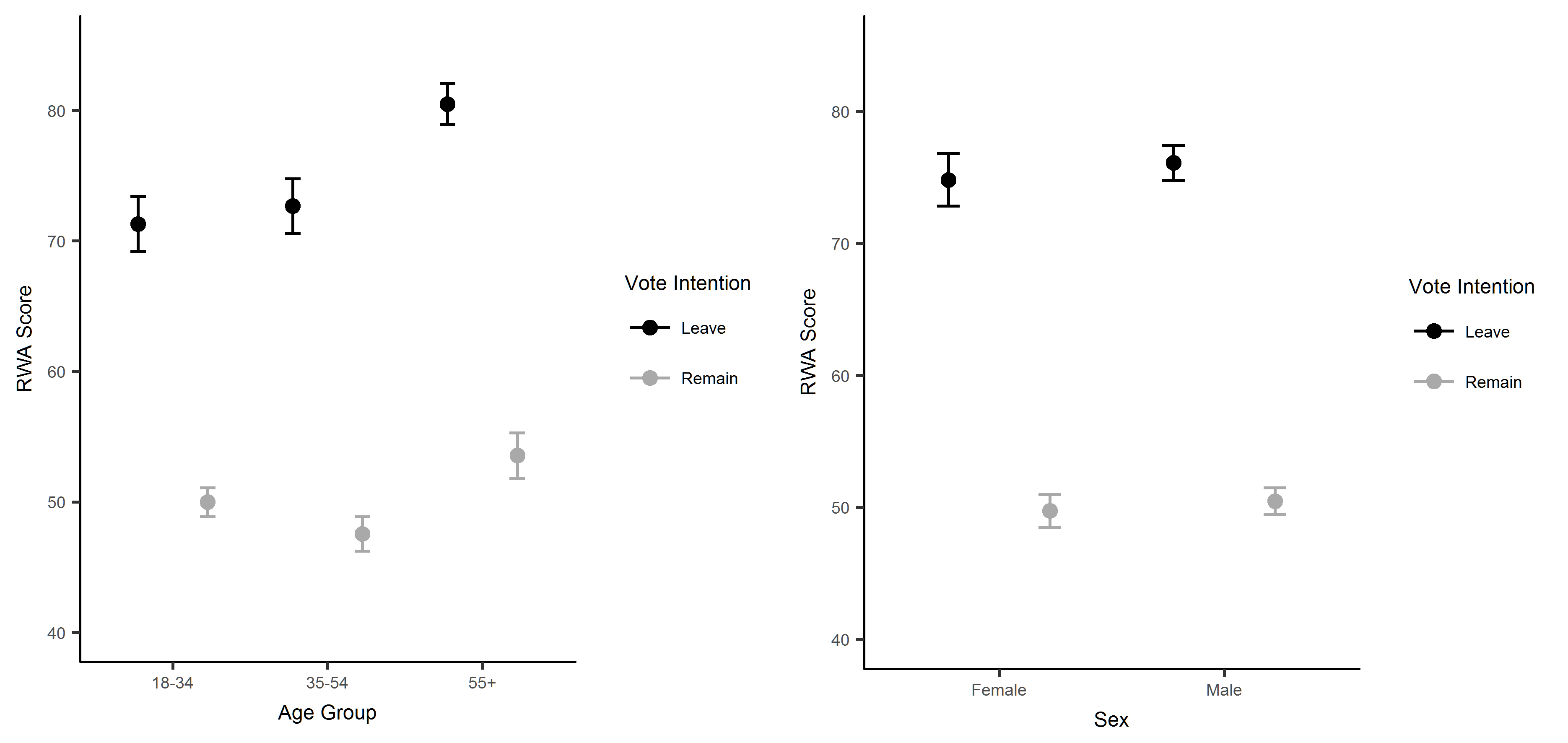

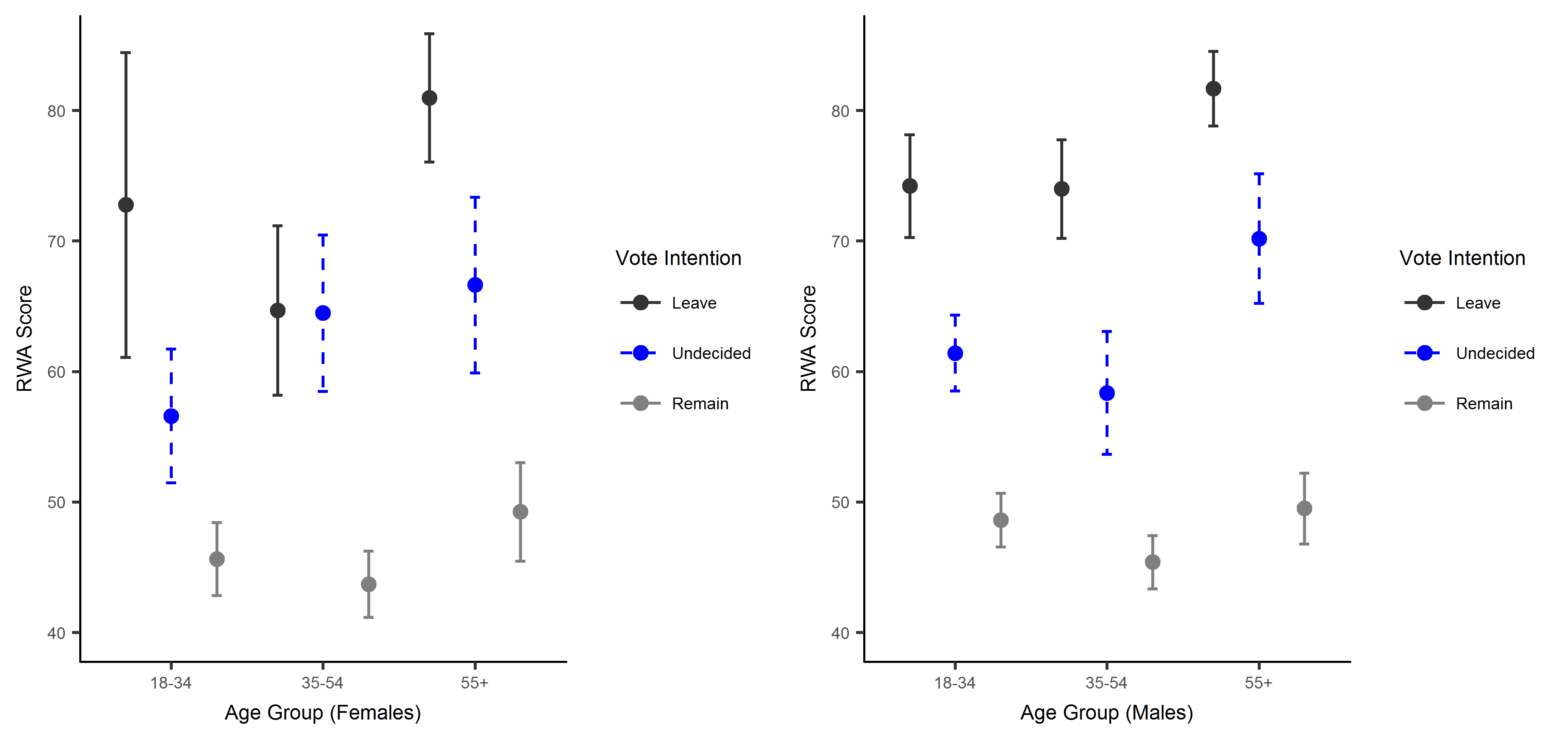

Participants expressing an intent to vote to leave the EU reported significantly higher levels of authoritarianism than voters expressing an intent to vote to remain.

Differences in Numeracy and Thinking Styles (Click images to enlarge)

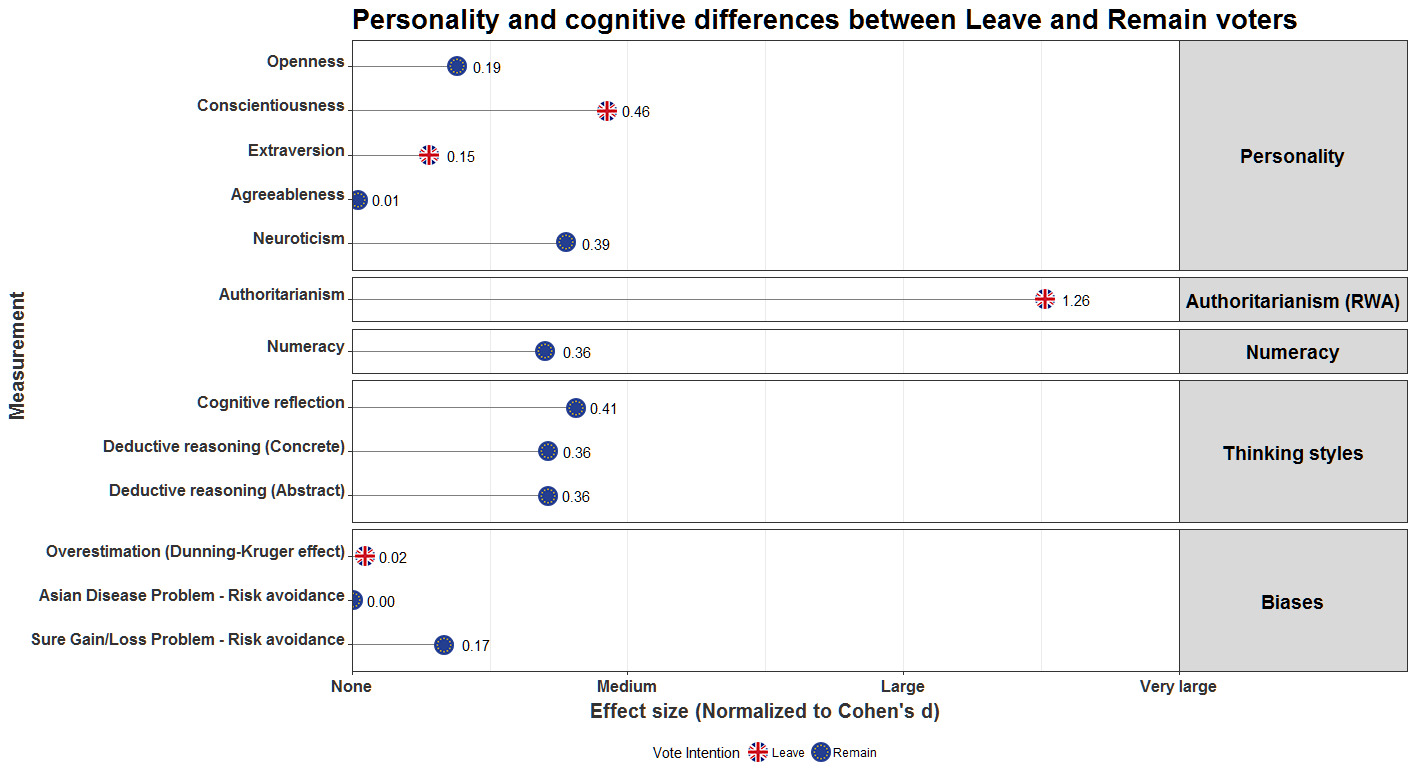

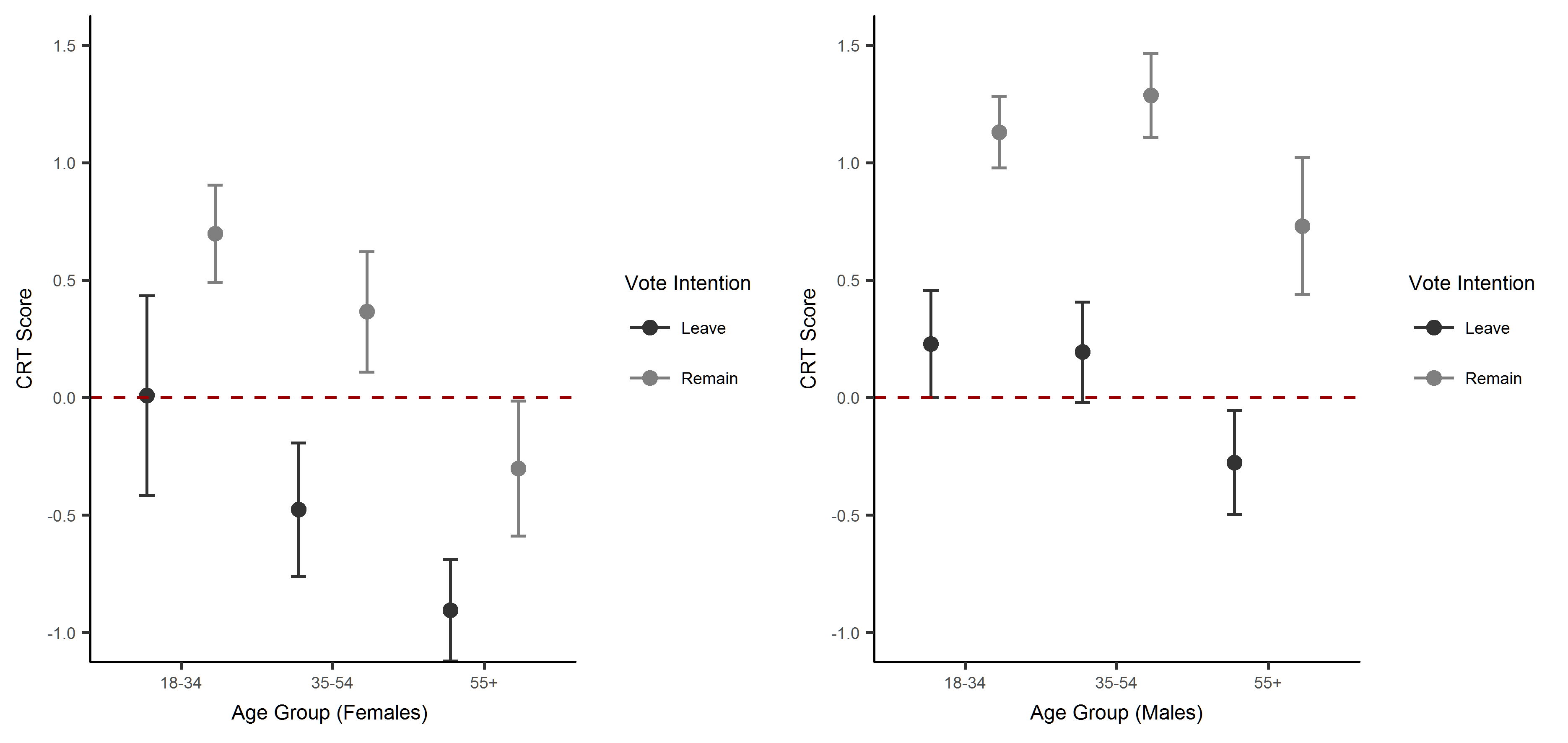

When compared to Leave voters, Remain voters had higher levels of numerical risk literacy, were more likely to engage in analytical System 2 thinking, and tended to perform better in deductive reasoning tasks. In all three areas, older voters tended to perform significantly worse than young voters intending to vote the same way.

Cognitive Reflection

Figure 7. Differences in Cognitive Reflection Test results for Leave and Remain voters by age group and sex. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval of the mean. Points below the dashed red line denote a greater tendency for impulsive System 1 thinking, while points above the red line denote a greater tendency for reflective System 2 thinking.

Cognitive Biases (Click images to enlarge)

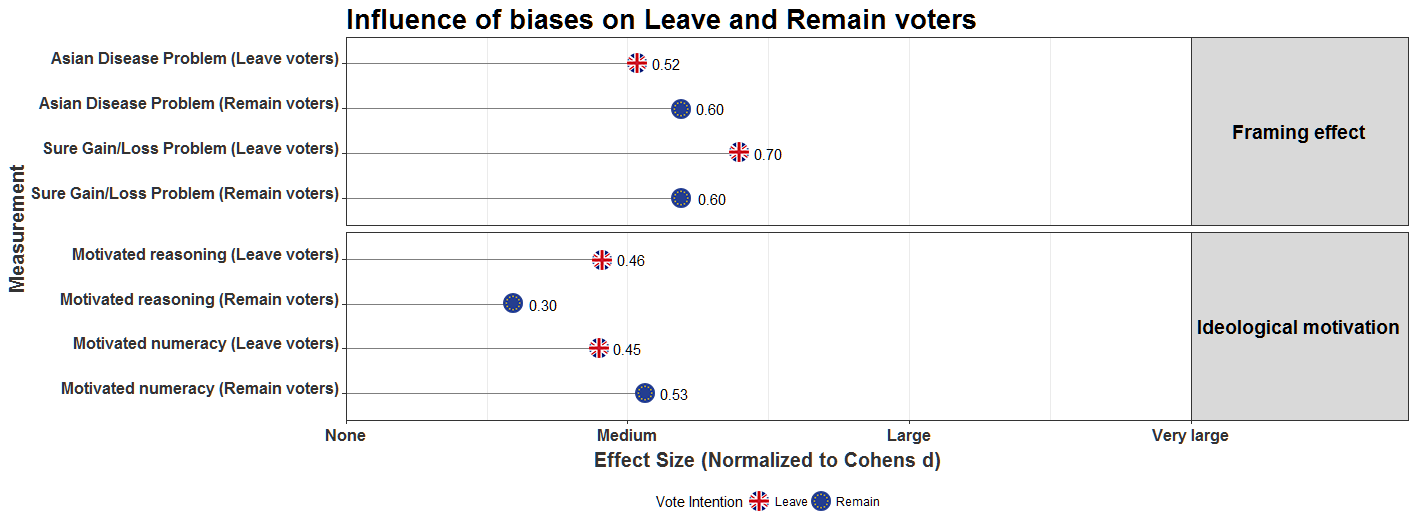

In the experimental studies, we found that both Leave and Remain voters were susceptible to ideologically motivated reasoning, ideologically motivated numeracy, framing, and the Dunning-Kruger effect. Unexpectedly and depending on the bias being tested, this susceptibility often differed slightly between voting camps. In general, older voters tended to be influenced by cognitive biases to a greater extent than younger voters intending to vote the same way.

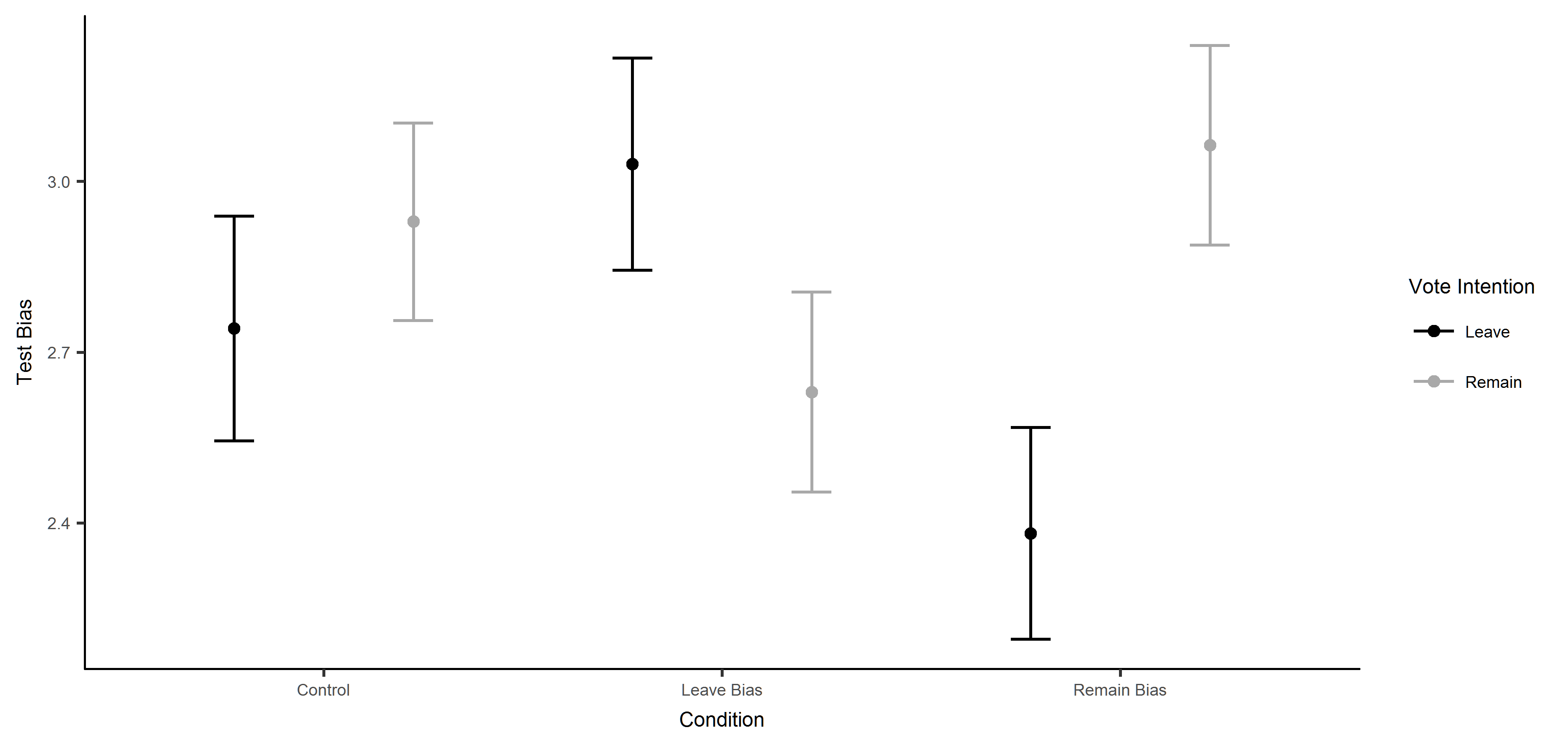

Ideologically Motivated Reasoning

Figure 9. Differences in levels of agreement with a post numeracy test statement for a given experimental condition. Experimental condition (Control, Leave Bias, Remain Bias) was designed to measure ideologically motivated reasoning, replicating Kahan et al. (2012). Error bars represent 95% confidence interval of the mean.

Both voting groups were less likely to agree with statements which were intended to challenge their beliefs. When comparing effect sizes, Leave voters displayed greater differences between the two experimental positions and therefore appear to be more susceptible to ideologically motivated reasoning.

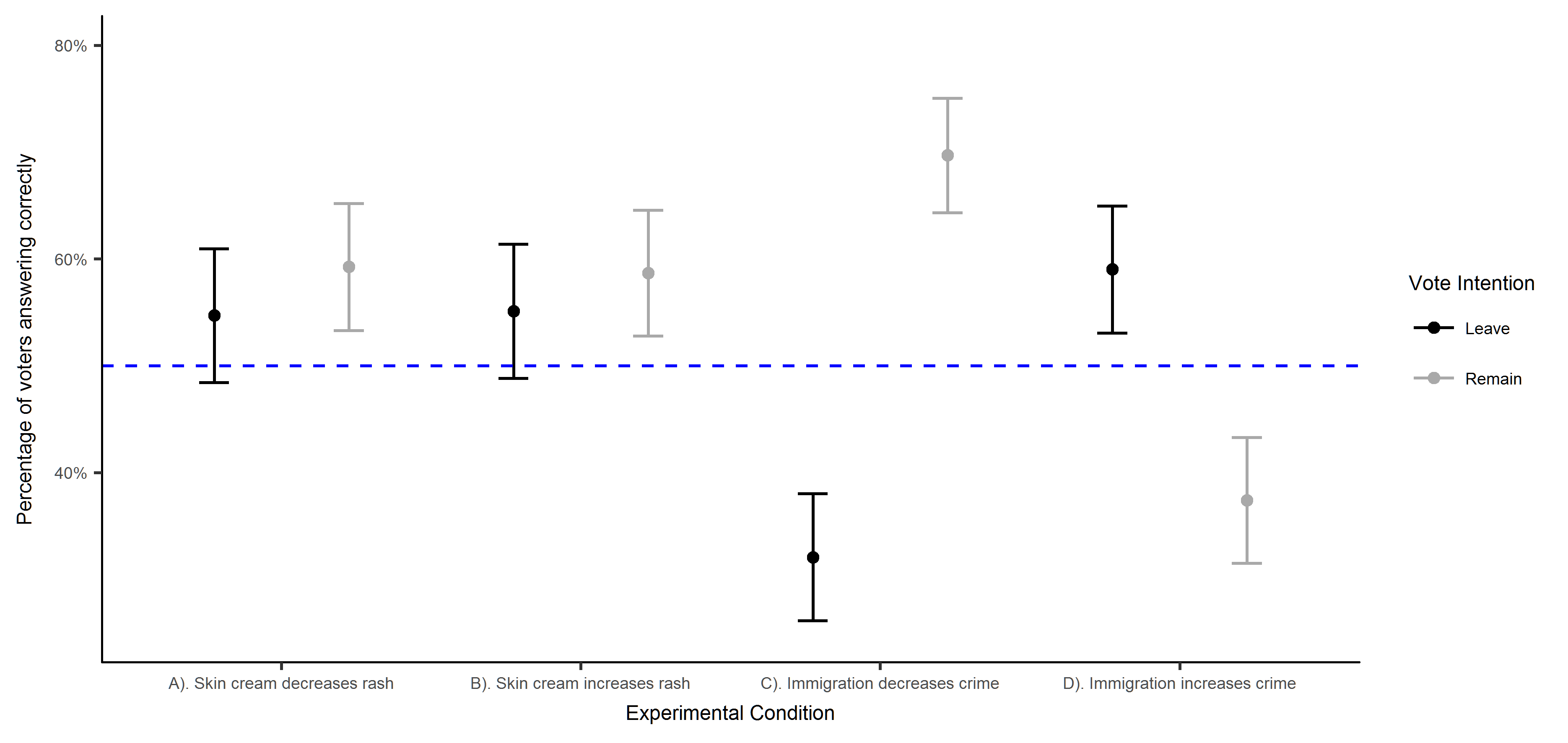

Ideologically Motivated Numeracy

Figure 10. Differences in numerical ability for a given experimental condition. Experimental condition was designed to measure ideologically motivated numeracy, replicating Kahan (2013). Error bars represent 95% confidence interval of the mean.

Both sides’ performance at interpreting numerical information drops similarly when the results did not support outcomes intended to resonate with their beliefs. When comparing effect sizes, Remain voters displayed a greater difference in performance between the two experimental positions and therefore appear to be more susceptible to ideologically motivated numeracy. Our findings are in line with Kahan (2013) who found that people with higher numerical literacy were more likely to engage in ideologically motivated numeracy.

The study replicated research by Yale Professor, Dan Kahan. Kahan’s research was dubbed ‘The Most Depressing Brain Finding Ever’.

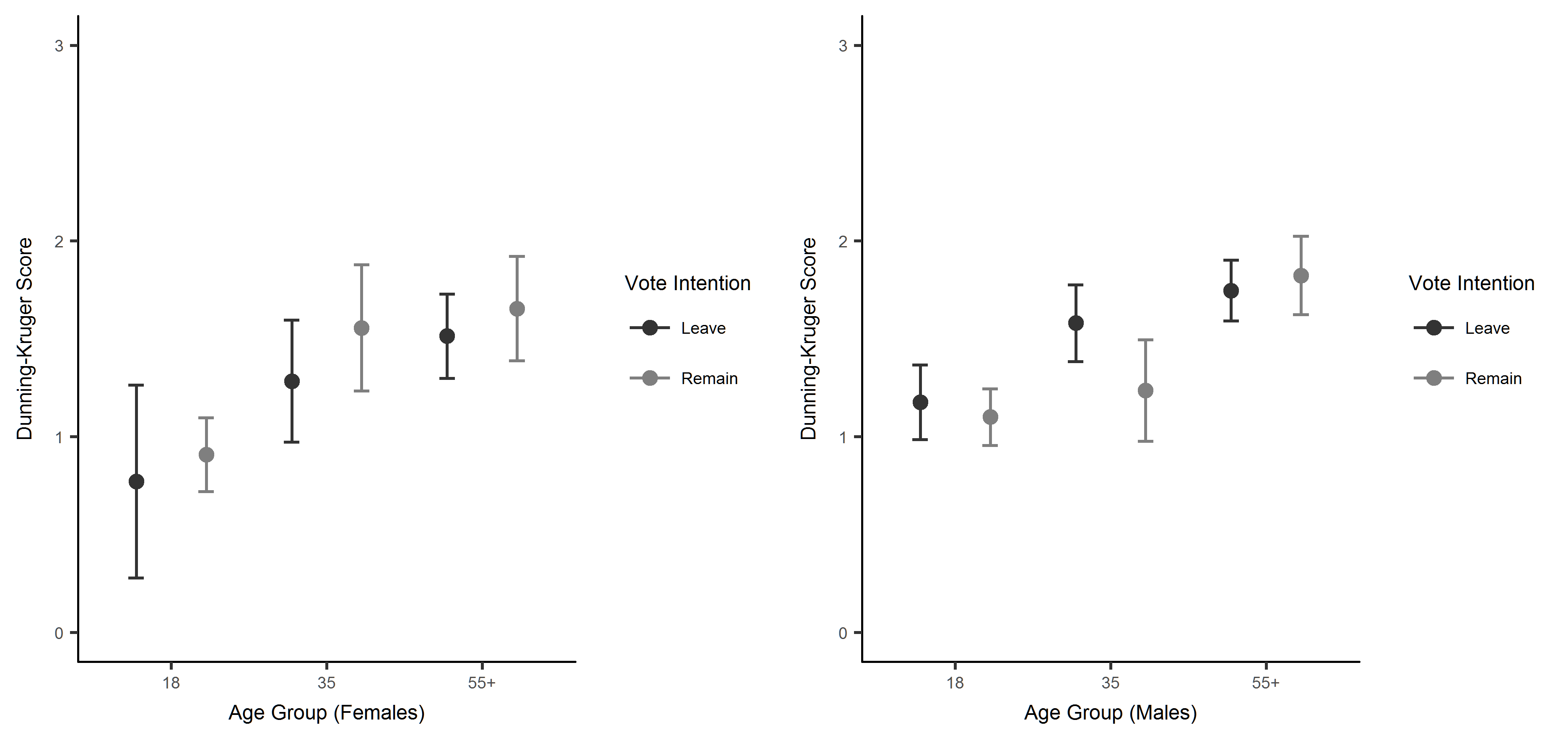

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

Figure 11. Differences in Dunning-Kruger scores (amount of overestimation) based on predicted Wason test scores minus participants’ actual scores. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval of the mean.

Considering males, Leave voters had higher scores than Remain voters, that is, male Leave voters appeared to be more susceptible to the Dunning-Kruger effect than Remain voters. Considering females, there were no significant differences between Leave and Remain voters.

Overall, participants 55 and older overestimated scores more than both participants aged 35-54 and 18-34. Participants 35-54 also overestimated scores more than participants 18-34.

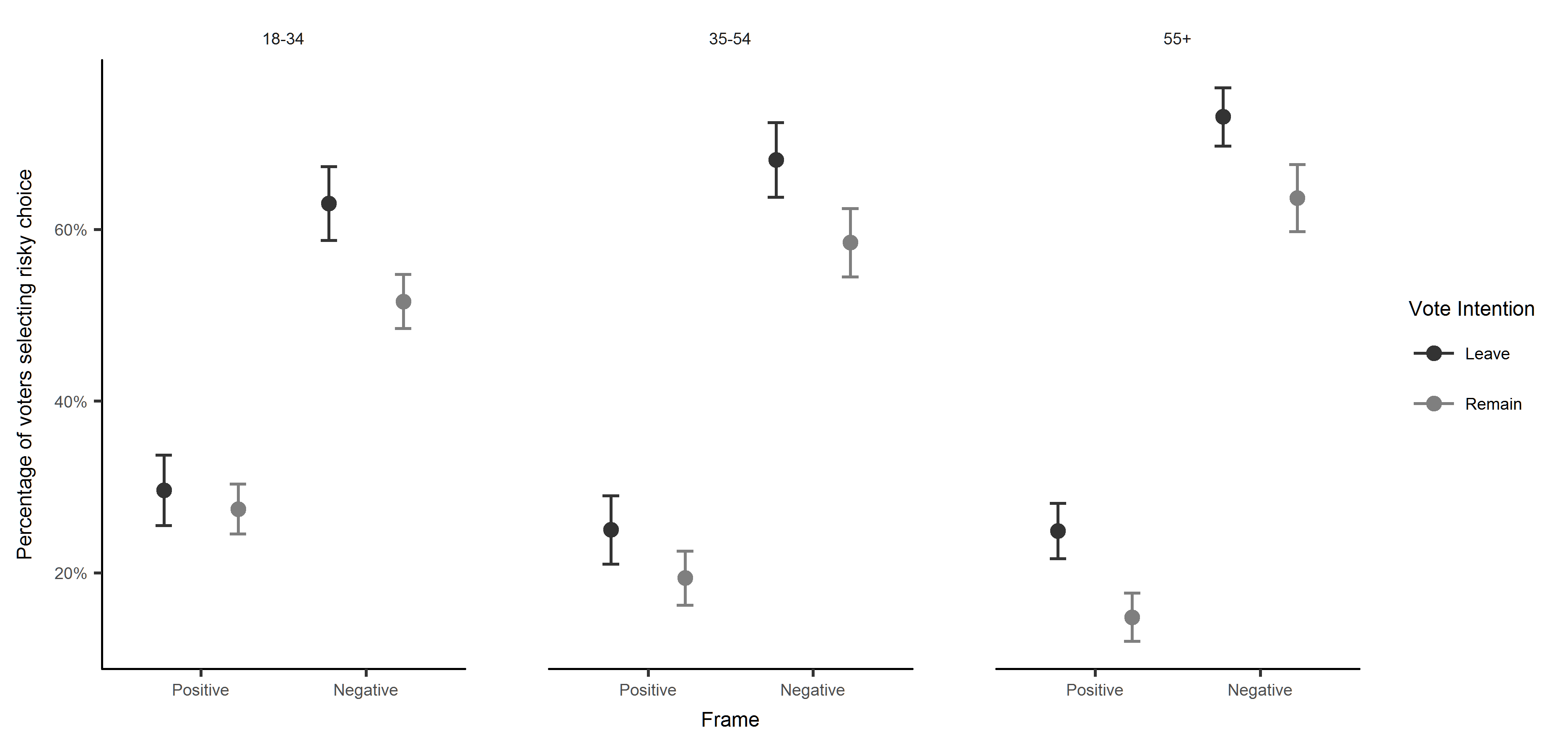

Framing

Figure 12. Differences in levels of risk-avoidance based on responses to Tversky and Kahneman’s (1981) Sure gains/Sure Loss problem (problem 3) by age group. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval of the mean.

The graphs illustrates voters tendency to choose the riskier of two options presented to them when the frame is negative. In this case, when presented with the positive frame, participants tend to prefer the risk-avoidant option. When presented with the negative frame, participants tend to chose the gamble.

We found that Leave voters appear to be influenced by the change in frame to a much greater extent than Remain voters. Leave voters were also more likely than Remain voters to choose the risky option for both positive and negative frames. This is not to say that Remain voters do not tend to choose the riskier option when presented with the negative Sure gain/Sure loss frame; they do, just to a lesser extent than Leave voters.

Additionally, participants aged 35-54 and 55 and above were more likely to choose the risky choice over younger participants.

Residual questions

These research findings raises a number of important questions:

- How appropriate and effective are referendums and other existing mechanisms for the public making political choices in the current digital age? In his paper titled ‘Referendums and deliberative democracy’ Professor Lawrence LeDuc offers discussion on this topic, noting that “Genuinely deliberative democracy requires that all arguments be heard equally”.

- In a situation where “In general, political campaign material in the UK is not regulated, and it is a matter for voters to decide on the basis of such material whether they consider it accurate or not” (The Electoral Commission, 2018) do regulatory controls need to be amended? At the time of writing, there are more restrictions about the claims advertisers can make about toothpaste then there are about political campaigns.

- Should access to and the use of social media and other personal online data be better regulated? but how do we ensure that we unleash the power of personal data for social good?

- How do we best channel information, provide clarifications on accuracy and interpretation, and inform open-minded rational public debate in an era of targeted ‘fake news’ and the potential online manipulation of people’s psychological traits?

- Do constitutions themselves need to be adapted to take into account fundamental shifts in societies’ use of technology and consumption of information?

Acknowledgements

The Online Privacy Foundation are very grateful for the assistance and partnership of John Scofield and Dr Erin Buchanan from the University of Missouri and Missouri State University respectively. Dr Buchanan maintains a wealth of statistics material which you can read more about here and view on her ‘Statistics of DOOM’ YouTube channel here. John maintains a github site with links to his research and code samples here.

The Online Privacy Foundation are additionally incredibly grateful for the time and assistance of everyone who contributed to this research project in one way or another.

Comments and additional material

Further supplemental material can be found on our Open Science Framework project page at https://osf.io/urt63/.

Contact chris@onlineprivacyfoundation.org for further information and/or if you have any feedback.

Notes:

For consideration in future drafts:

RWA scale: A future iteration of this paper will acknowledge the criticisms of the RWA scale which may explain the large effect sizes noted. Specifically, “Other criticisms of the RWA scale stem from the fact that many of the items are similar to dependent measures that authoritarianism was meant to predict, such as tolerance and prejudice (Feldman, 2003; Oesterreich, 2005) “. Dunwoody, P. T., & Funke, F. (2016). The Aggression-Submission-Conventionalism scale: Testing a new three factor measure of authoritarianism. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 4(2), 571-600

Complementary research: Since publishing our working paper, we have been made aware of the following complementary research:

Zmigrod, L., Rentfrow, P. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2018). Cognitive underpinnings of nationalistic ideology in the context of Brexit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201708960.

Garretsen, H., Stoker, J. I., Soudis, D., Martin, R. L., & Rentfrow, P. J. (2018). Brexit and the relevance of regional personality traits: more psychological Openness could have swung the regional vote. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 165-175.

Harper, C. A., & Hogue, T. (2018). The role of intuitive moral foundations in Britain’s Brexit vote. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/3ch9v

Veltri, G. A., Redd, R., Mannarini, T., & Salvatore, S. (2019). The identity of Brexit: A cultural psychology analysis. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 29(1), 18-31.

Richards, M. (2019), What is the Right-Wing Press?. In towardsdatascience.com

General notes:

Effect size: “Another way to interpret effect sizes is to compare them to the effect sizes of differences that are familiar. For example, Cohen (1969, p23) describes an effect size of 0.2 as ‘small’ and gives to illustrate it the example that the difference between the heights of 15 year old and 16 year old girls in the US corresponds to an effect of this size. An effect size of 0.5 is described as ‘medium’ and is ‘large enough to be visible to the naked eye’. A 0.5 effect size corresponds to the difference between the heights of 14 year old and 18 year old girls. Cohen describes an effect size of 0.8 as ‘grossly perceptible and therefore large’ and equates it to the difference between the heights of 13 year old and 18 year old girls. As a further example he states that the difference in IQ between holders of the Ph.D. degree and ‘typical college freshmen’ is comparable to an effect size of 0.8.” – Source: Coe, R. (2002). It’s the effect size, stupid: What effect size is and why it is important (https://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00002182.htm).

Groups versus individuals: In interpreting these results, it would be easy to conclude that Leave and Remain voters are polar opposites. When we talk about differences, what we really mean is that the “average” or “typical” Leave voter is different than the “average” or “typical” Remain voter. The following density plot shows that while there are clear differences in levels of authoritarianism, there is also a lot of overlap.